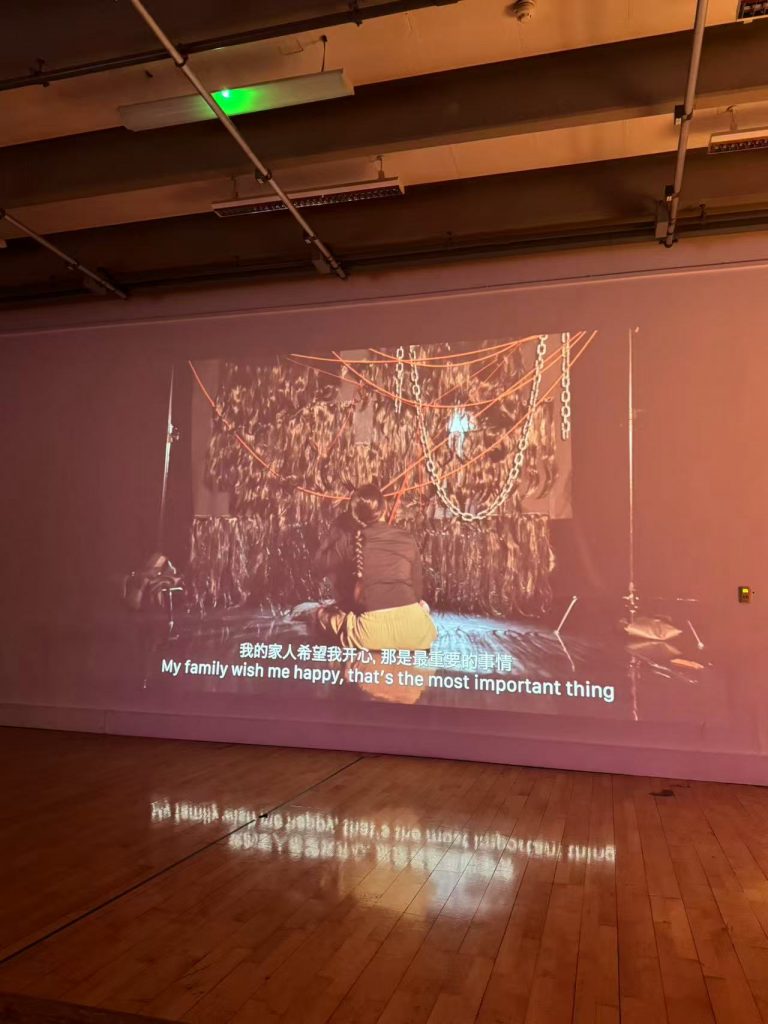

This week, my installation and collaboratively created screendance film are exhibited at the FRAME SHIFT showcase at London Contemporary Dance School (The Place).

The work consists of three interdependent components: installation + co-created film + embodied practice.

Installation:

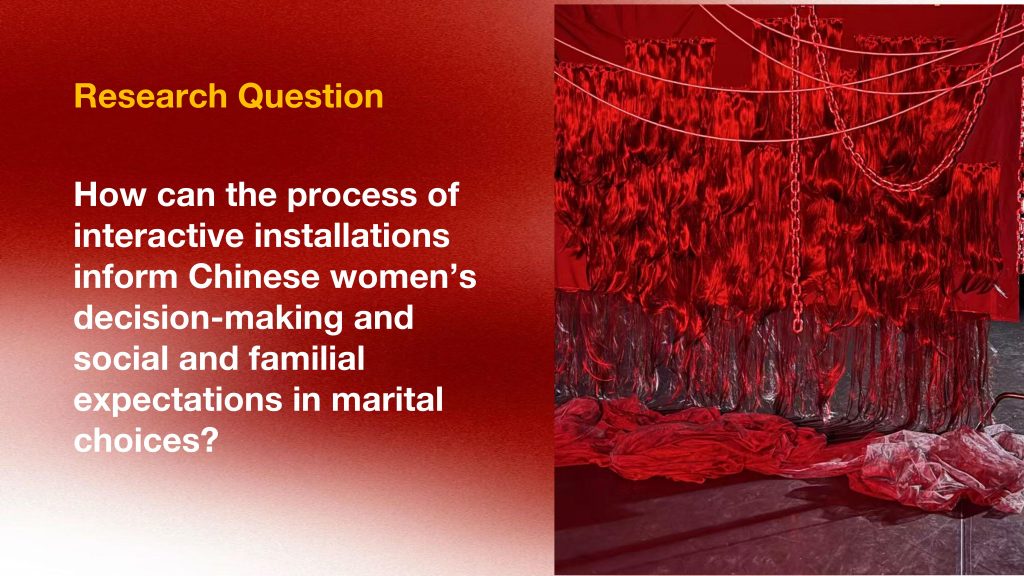

Constructed using hair, red thread and fabric as primary materials, the installation builds a spatial environment that addresses marriage, the female body and socially conditioned expectations.

Co-created film:

Developed collaboratively with dancers and filmed within the installation, the work positions the interaction between movement and material as the central narrative mechanism, rather than as documentation of performance.

Movement vocabulary:

Derived from everyday postures, repetitive labour and ritualised gestures associated with the female body, this vocabulary informs both the film and the designed pathway of audience engagement within the exhibition space.

Together, the three components operate relationally:

the installation serves as a site for bodily experience;

the film extends the temporal trace of bodily–material interaction;

and the movement vocabulary provides a structural framework for navigating the relationship between installation and film.

The most research-significant aspect of this exhibition emerged through the audience’s immediate responses—emotional, behavioural and embodied reactions that exceeded what is typically observed in installation-based exhibitions. One viewer experienced a notable emotional breakdown after engaging with both the film and the installation narrative.

Unexpectedly, several older visitors (60+) did not interpret the work primarily as a critique of marriage. Instead, they described it as an invitation to reconsider intimacy, relational autonomy and personal worth.

On-site feedback suggests that meaning is not contained within the work itself, but is continuously reconstructed through the audience’s interaction—emotionally, cognitively and physically—with the piece.