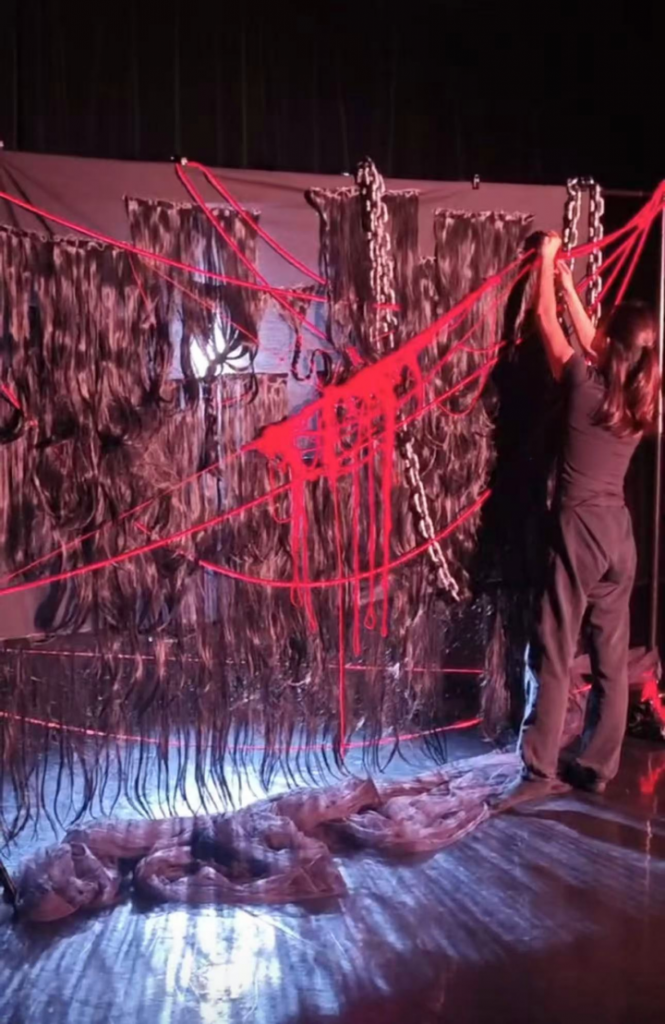

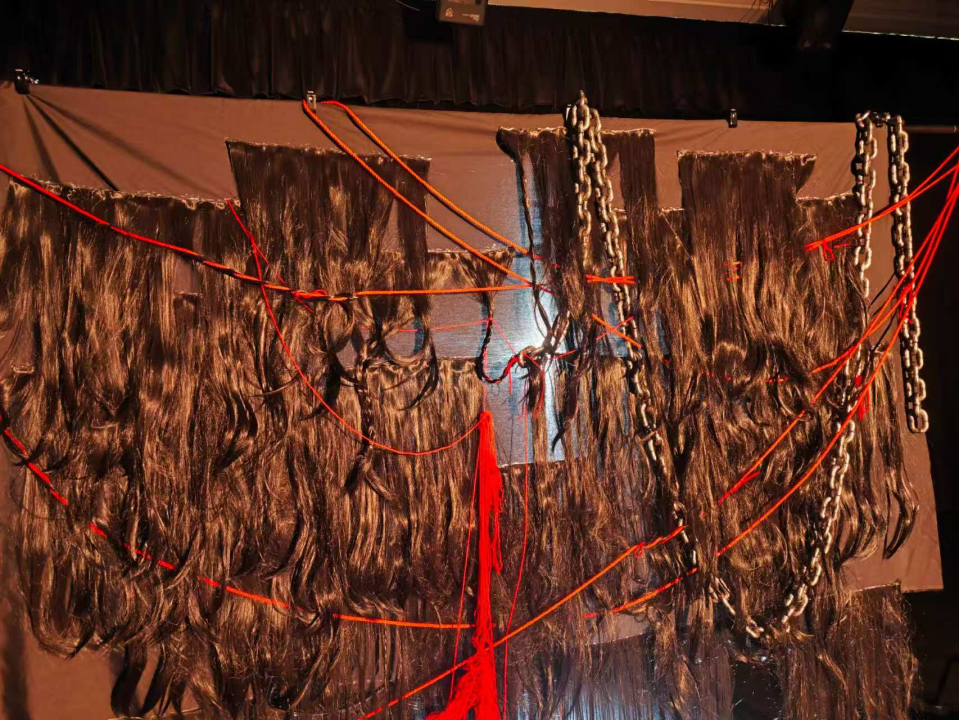

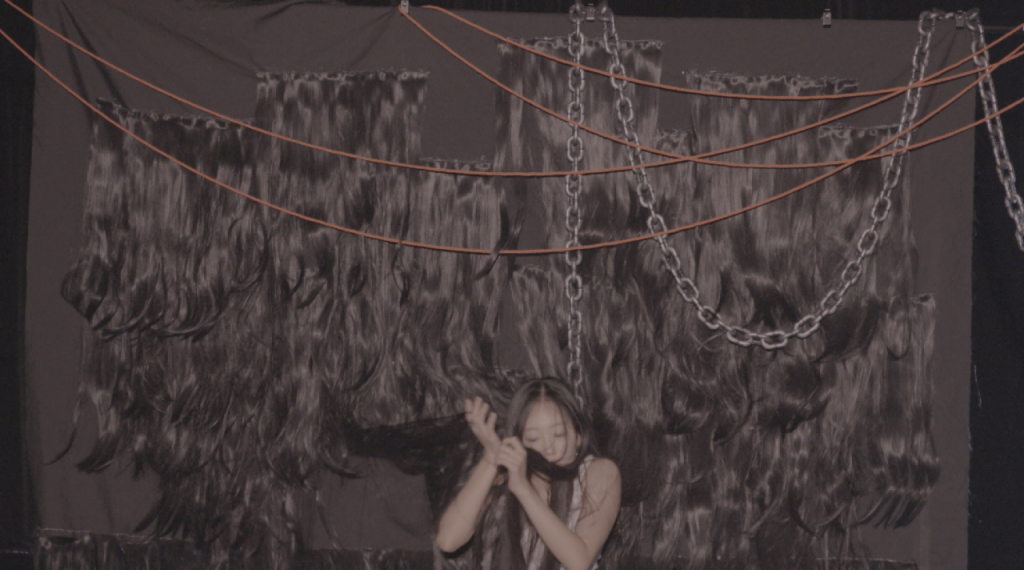

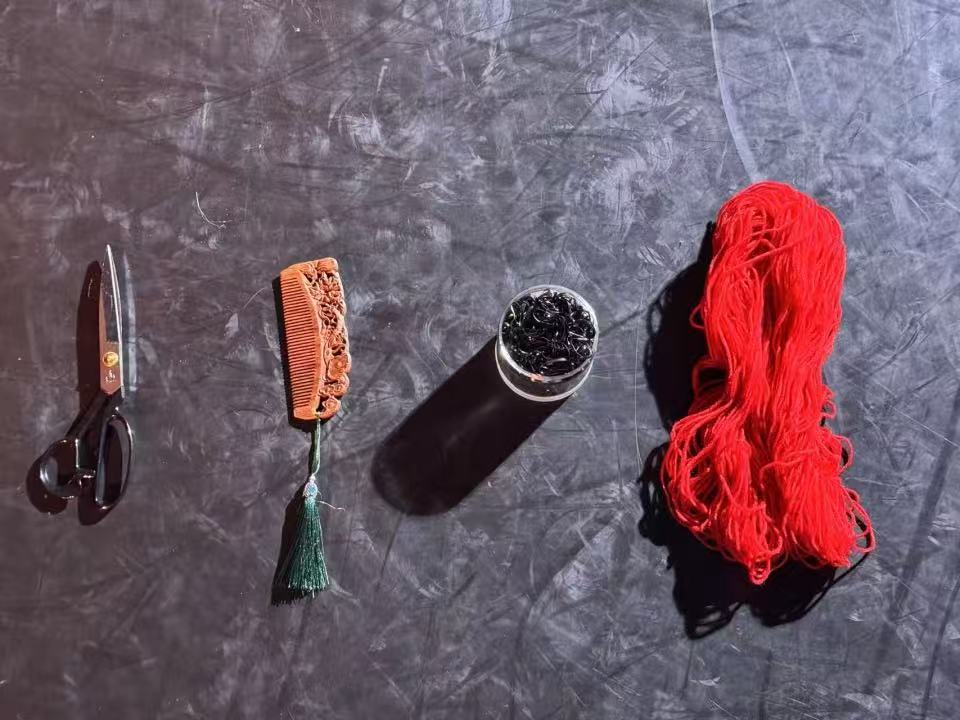

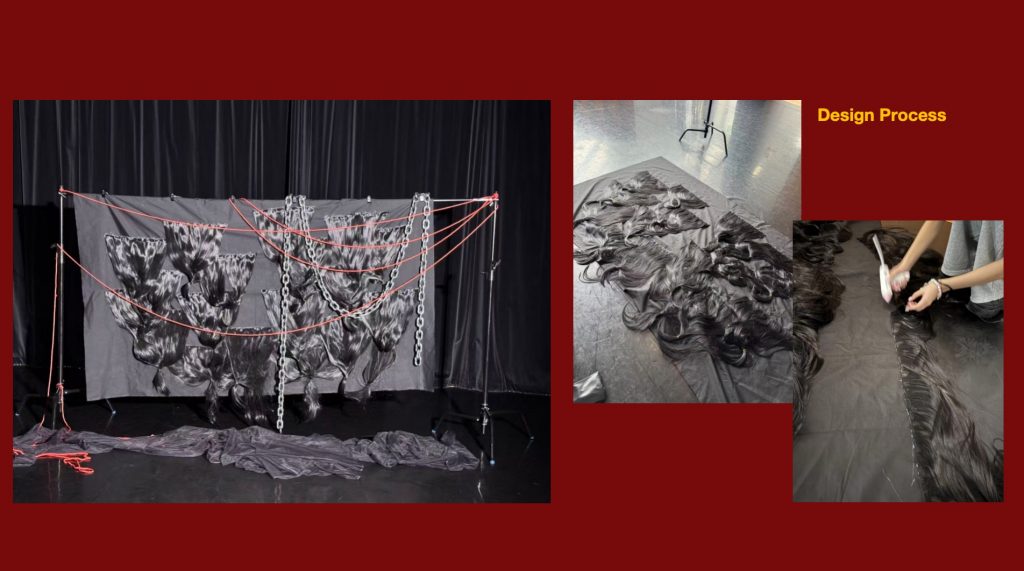

My recent installation continues my exploration of Chinese women’s marriage systems and their structural implications. The work is composed of red satin, lace, tulle, combs, and scissors, and invites the audience to participate through actions such as braiding, winding, and cutting. Through these bodily interactions, I hope participants can physically experience the restrictions imposed on women by marriage and social structures, and reflect on the tension between constraint and liberation.

The inspiration for this installation comes from a unique group of women in modern Chinese history—the self-combing women (zishunü). They were most active from the late Qing dynasty to the first half of the twentieth century, especially in the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong, such as Shunde, Nanhai, Panyu, and Jiangmen, where the silk-reeling industry flourished. At that time, textile production required a large female workforce, enabling many women to achieve economic independence through their labor rather than relying entirely on family or marriage.

The name “self-combing women” derives from the coming-of-age ritual in which they would comb their own hair into a bun, symbolizing adulthood and solemnly declaring a lifelong decision not to marry. This choice was both an act of resistance against patriarchal marriage structures and a survival strategy within specific economic conditions. Many of them lived together in small communities, supporting and caring for one another into old age. Yet their lifestyle was often stigmatized, branded as “unfilial” or “deviant” under prevailing social norms.

In my installation, I deliberately incorporate elements such as hair, binding fabrics, and red threads to extend these historical metaphors into a contemporary context:

- Hair serves as a marker of female identity and the body.

- Binding fabrics—red satin, ribbons, and lace—symbolize the constraints of social and marital systems.

- Red threads function both as metaphors of emotion and destiny, and as tangible forms of entanglement and rupture through the audience’s participation in braiding, winding, and cutting.

Between history and the present, I hope this work becomes a metaphorical space: one that carries the solitary courage of the self-combing women while also reflecting the dilemmas and negotiations that contemporary women continue to face.