When discussing the pressure to get married, people often attribute it to societal norms, cultural traditions, or policy-driven expectations. However, throughout my field research, another source emerged repeatedly—one that is more intimate, emotionally charged, and deeply rooted: the expectations that come from within the family.

Across a series of in-depth interviews, I found that the strongest pressure to marry often comes from female elders—mothers and grandmothers—rather than from fathers or male relatives. This finding was both unexpected and thought-provoking: Why do women from the previous generation become the primary agents of marital pressure?

To understand this phenomenon, I conducted a focused interview to explore why female family members so often act as the key drivers of urging marriage.

One interviewee shared that the greatest pressure she felt to get married did not come from her father, but from her mother and grandmother. Her mother firmly believed that “marriage is something every woman must go through.”When the interviewee expressed that she was not ready for marriage, her mother replied:

“Once you get married, life becomes stable. A woman only feels secure when she has her own family.”

The interviewee emphasised that her mother was not intentionally forcing her into marriage; rather, this belief stemmed from her mother’s own lived experience—that marriage had brought her happiness and security. She said:

“My mum is part of the generation whose life genuinely improved after marriage. She and my dad became financially stable, their relationship was harmonious, and life got better. So she truly believes marriage is a good thing for women.”

For her mother’s generation, marriage indeed served as a form of upward social mobility. Many women gained access to resources, social status, and a sense of security through marriage. In this context, marriage was not a limitation, but a means of “escaping hardship” and “achieving a better life.”

As the interviewee concluded:

“She wants me to take the same path because it is the only route to happiness she has ever known.”

Why Did the Previous Generation Believe Marriage Was the Path to Happiness?

To understand the marriage values held by women of previous generations, we must return to the socio-historical environment in which their beliefs were formed. Through conversations with women from my participants’ parents’ generation, it became clear that “marriage brings happiness” was not an imagined ideal, but a lived reality rooted in the social structure, economic conditions, and gender norms of the time.

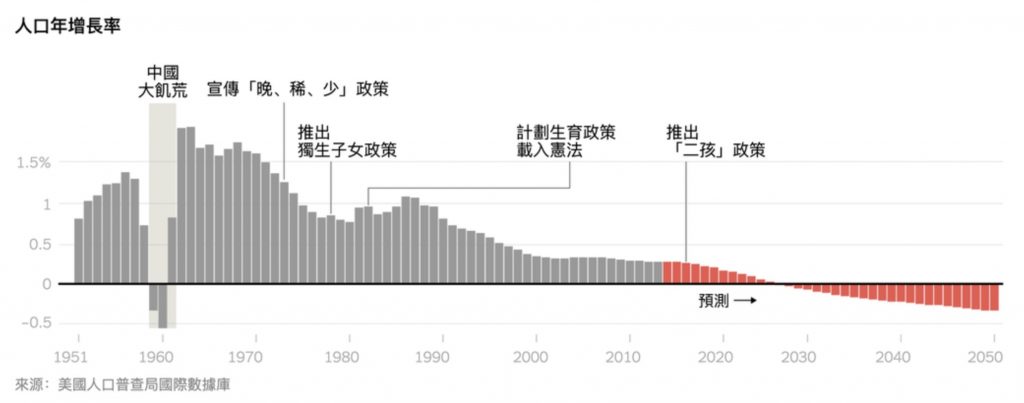

In the 1980s–1990s, traditional gendered division of labour remained dominant in Chinese households: men were expected to be the primary breadwinners, while women carried out domestic and caregiving roles (Yan, 2003). Within this structure, women’s social value and personal security were largely tied to marriage and family roles, rather than to independent career development. Marriage was not merely a romantic relationship—it functioned as a form of practical life security.

Furthermore, the post–reform economic boom significantly improved living standards. Many women experienced tangible life improvements after marriage—better housing, increased family income, enhanced social welfare, and greater financial stability (Zhang, 2010). For them, marriage truly resulted in visible, measurable gains. Under these conditions, viewing marriage as a reliable route to stability and happiness was both reasonable and beneficial.

As a result, women of that generation genuinely believed—on the basis of their own lived experiences—that marriage equalled stability, happiness, and “having someone to rely on.” Yet this sense of happiness was shaped by historical and structural conditions, not by marriage itself.

However, it is important to recognise that this model of “marital happiness” was built on a highly gendered family structure: women exchanged domestic labour and caregiving for men’s financial provision (Fong, 2004). This exchange shaped their worldview and informed how they advised their daughters.

In other words, their insistence that “marriage is good for women” did not arise from control or conservatism, but rather because—in their time—marriage was the most reliable and socially sanctioned pathway for a woman to secure a good life.

References

Fong, V. (2004) Only Hope: Coming of Age under China’s One-Child Policy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Yan, Y. (2003) Private Life under Socialism: Love, Intimacy, and Family Change in a Chinese Village, 1949–1999. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Zhang, L. (2010) In Search of Paradise: Middle-Class Living in a Chinese Metropolis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.