Introduction

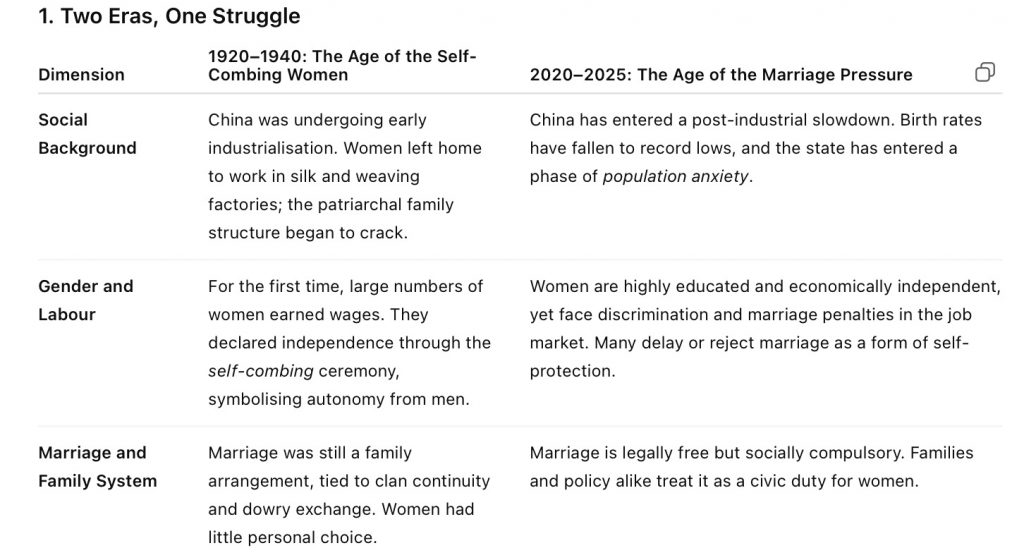

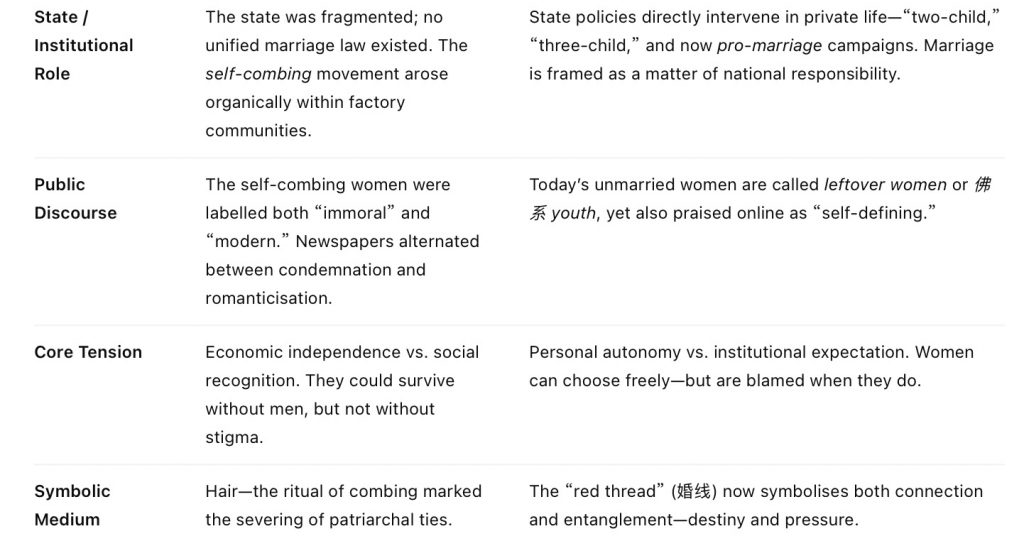

When I began studying the self-combing women (自梳女) of southern China, active between the 1920s and 1940s, I was struck by an eerie sense of repetition.

These women—textile workers in Guangdong and Hong Kong—refused to marry, choosing to earn their own living and declare lifelong celibacy through a ritual act of “self-combing.”

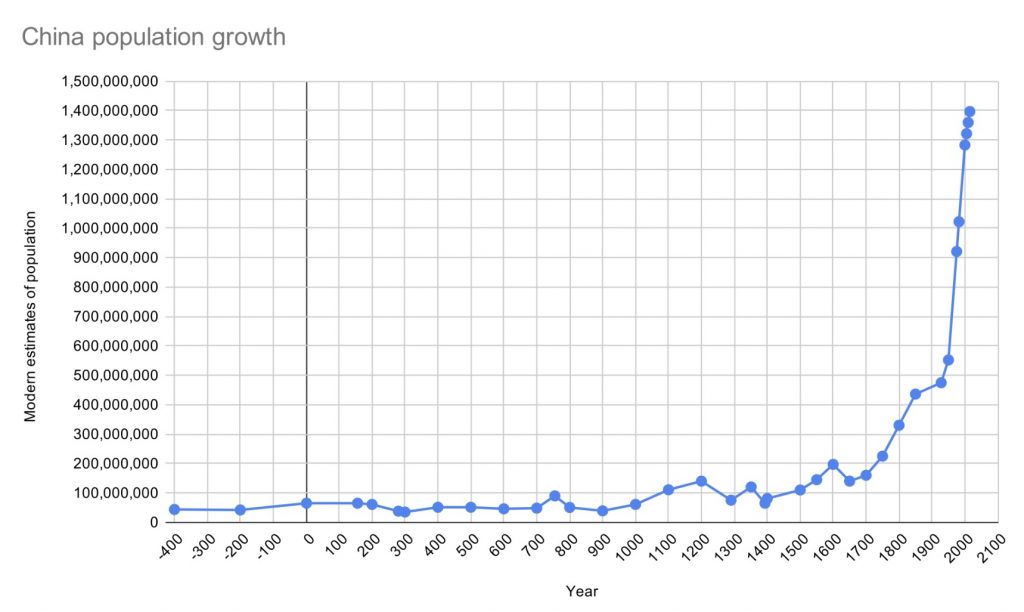

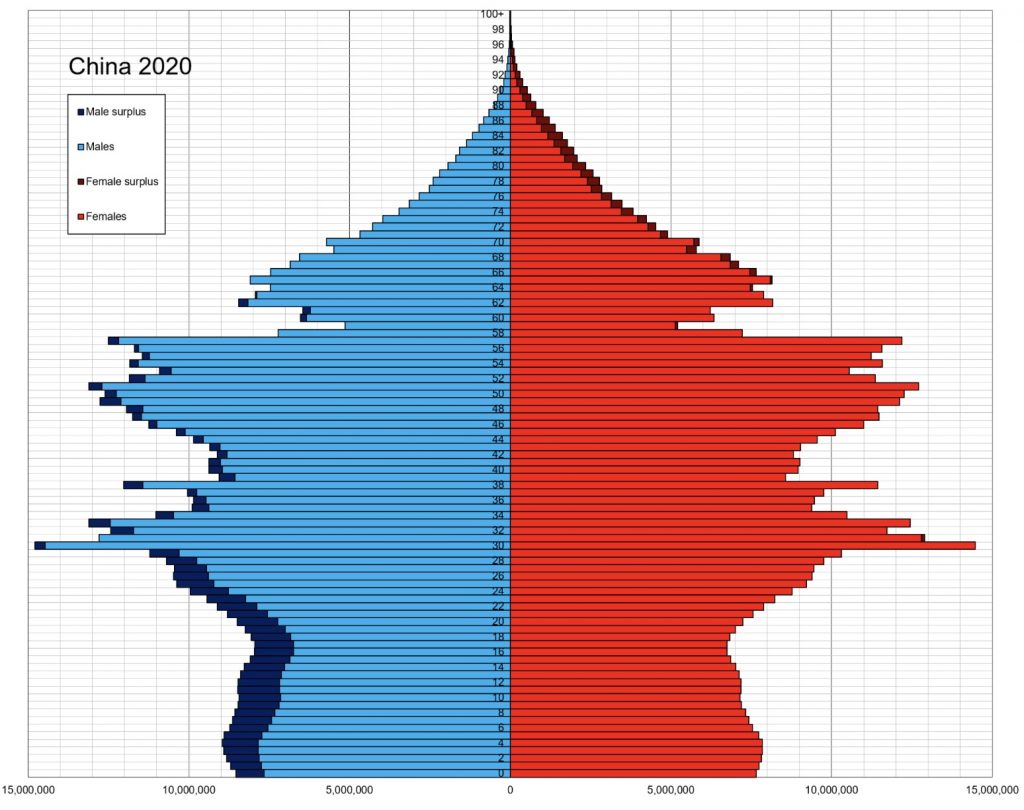

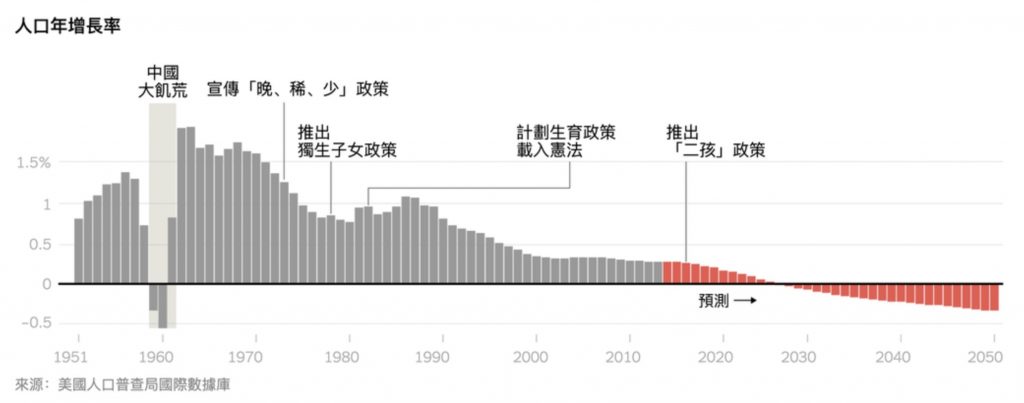

Almost a century later, in 2025, Chinese women once again find themselves under intense social and policy pressure to marry and give birth.

Why do different generations of women, separated by time and social systems, face the same question of whether to marry at all?

To answer this, we need to trace the structural logic behind both eras—how economy, family, policy, and ideology shape the meaning of “womanhood” in different historical moments.

2. The Repeating Structure of Control

Across both eras, the same triangular power structure reappears:

State → Family → Female Body

Whenever women’s labour or bodies move outside this structure, society reacts with anxiety.

In the 1920s, it was the fear of women leaving the family economy.

In the 2020s, it is the fear of women leaving the reproductive economy.

The form of pressure has changed—from open patriarchal control to “soft persuasion” through policy and media—but the underlying logic remains:

The freedom of women becomes visible only when it threatens existing systems.

- The Repeating Structure of Control

Across both eras, the same triangular power structure reappears:

State → Family → Female Body

Whenever women’s labour or bodies move outside this structure, society reacts with anxiety.

In the 1920s, it was the fear of women leaving the family economy.

In the 2020s, it is the fear of women leaving the reproductive economy.

The form of pressure has changed—from open patriarchal control to “soft persuasion” through policy and media—but the underlying logic remains:

The freedom of women becomes visible only when it threatens existing systems. - Resistance as Continuum

Both groups of women, though separated by a century, chose resistance through life design rather than protest.

The self-combing women ritualised independence through their hair, creating female communes that redefined kinship.

Contemporary women ritualise independence through their lifestyle—education, career, and the right not to marry or give birth.

In both cases, resistance is domestic, embodied, and deeply personal.

It transforms private choices into social statements.

The line connecting these points is cyclical:

when women gain autonomy, the system tightens control.

Leave a Reply